Flamenco isn’t just music, dance, or song—it’s something else entirely. A pulse. A heartbeat. A fire in the blood.

But where did it come from?

Ask ten people, you’ll get ten answers. That’s because flamenco’s origins aren’t neatly written down in history books. They live in echoes. In stories passed down. In rhythms carved out of survival.

What we do know is that flamenco was born in Andalusia, in Spain’s sun-scorched south. But it wasn’t just one thing.

It was a clash of cultures, tangled together, each leaving something behind.

The deep, wailing melodies of the Moors. The sorrowful chants of Sephardic Jews. The fiery, relentless rhythms and musical scales of the Romani people. It’s all in there.

The Roma, or Gitanos as they’re called in Spain, arrived in the 1400s from India. They brought their own music, their own soul. The Moors had already been in Andalusia for centuries, their influence soaking into the sound of the land through instruments like the guitar.

Every group, every culture, every soul that was pushed to the margins poured their pain into song. That’s flamenco.

Much of its early history? Gone. Lost. The Gitanos passed it down through word of mouth, not paper. The Moors? Granada fell in 1492, and with the expulsion of the Moors from 1609-614 their presence was scrubbed from the record. The Jews? Forced into hiding. Even Christopher Columbus—turns out, he might have had Jewish roots, keeping his true identity under wraps because it wasn’t safe to be anything else.

So flamenco survived not in books, but in the people. In their voices. In the music.

Even the word “flamenco” is a bit of a mystery. Some reckon it comes from the Flemish people (flamencos in Spanish), a theory kicked around by English writer George Borrow in the 1830s. Others, like Andalusian historian Blas Infante, argue it’s from the Arabic “felah mengu”—meaning “wandering peasant.” If he’s right, flamenco’s roots run even deeper into Moorish history than we thought.

The first written mention of flamenco? 1774, in “Cartas Marruecas” by José Cadalso. But back then, it wasn’t even about music. It wasn’t until 1847 that “flamenco” was used to describe song and dance. Even then, it was just the “gitano genre.”

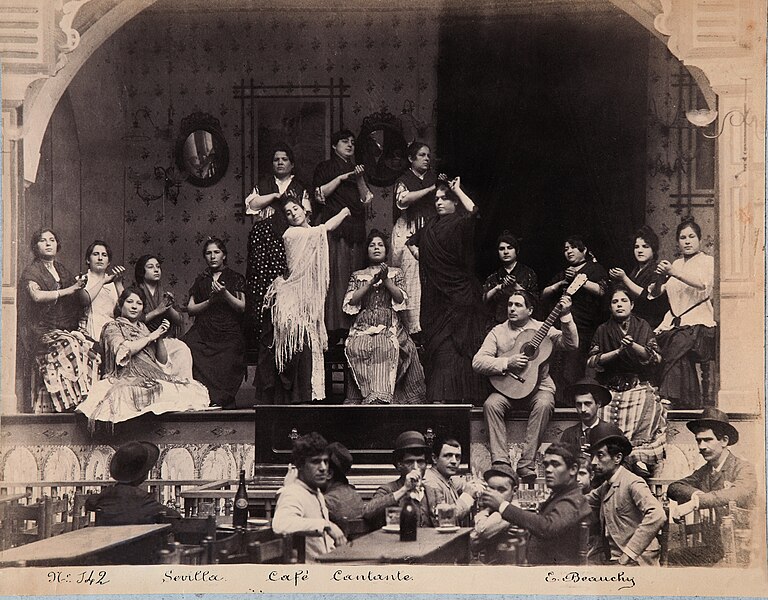

Then, between 1869 and 1910, flamenco exploded. It found its place in cafés cantantes—small, smoky venues where singers, dancers, and guitarists took the stage and left audiences spellbound.

The first flamenco café opened in Seville in 1881, thanks to singer Silverio Franconetti. After that, it spread like wildfire. Dance took centre stage. Guitarists pushed the boundaries.

Flamenco evolved, fast.

By the early 20th century, it had outgrown the cafés and landed on grand stages—bullrings, theatres, concert halls. With success came change.

Lighter, more accessible styles like cantiñas and fandangos emerged. The guitar—whose roots go back to the Moorish oud—became the star, adding new depth and complexity to the music.

But flamenco never quite sat right with Spain’s elite.

Too raw.

Too tied to the working class, to the Gitanos.

But this antagonism pre-dates the 20th century. After the Spanish War of Independence (1808-1812), Spain’s national identity was shifting. Bullfighting, flamenco, and “flamenquismo”—a kind of exaggerated Andalusian aesthetic—became symbols of Spanish pride as a reaction to Frenchified Spanish elites.

Ironic, really. The music of the oppressed, now being used to define a nation.

This push-and-pull tension remains to this day.

After the Spanish Civil War the Catholic church did not like flamenco and all that it meant. But in the 1950s, Franco’s dictatorship realised flamenco could fill their empty pockets. It could sell a dream—passion, mystery, the fiery soul of Spain. So they used it. Promoted it. Flamenco tablaos were set up for tourists, dancers were shipped off to perform abroad, glossy airline brochures plastered with flamenco imagery.

One tourism promoter put it bluntly: “The day we lose Spanish stereotypes, we will have lost 90% of our attraction for tourists.”

So Spain, once again, leaned on the myth.

Flamenco became the face of an imagined, romantic Spain. And a cultural tradition that non-Romani Spaniards could call their own as well.

Was that a bad thing? Not necessarily. One of Spain’s greatest-ever musical exports was Paco de Lucía, the incredible guitar player from souther Andalusia. No gypsy heritage. But a flamenco legend all the same.

So does a “real” flamenco exist? To many, yes. It stayed where it had always been. In the “Golden Triangle”—Cádiz, Jerez de la Frontera, and Triana in Seville. This was the home of Cante Jondo, the deepest, rawest, most gut-wrenching style of flamenco.

The sound of struggle. Of longing. You can still find it if you look hard enough.

On November 16, 2010, UNESCO finally recognised what the world already knew—flamenco is one of Spain’s greatest cultural treasures. A masterpiece of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity. A living, breathing art form that refuses to be tamed.

But the contradictions remain.

Flamenco is loved worldwide, but the Gitanos who shaped it still face discrimination. The music is celebrated, yet its history—its messy, inconvenient truth—often gets brushed aside.

Even pop culture can’t resist flamenco’s pull. When Buzz Lightyear switched to “Spanish mode” in Toy Story 3, he didn’t dance a jota. Or a sardana.

He danced flamenco.

Flamenco was never meant to represent Spain, but somehow, it does. Born on the fringes, carried forward by those who had nothing else, it lives on.

Like jazz and blues in America—once dismissed as the music of the lower classes, now revered as high art—flamenco has outlasted its critics. It has survived.

And it’s still wild. Still defiant. Still impossible to contain.

The story of flamenco isn’t over.

What we hear today? Just another chapter in a tale that began centuries ago. A story of cultures colliding, of voices that refused to be silenced. And still won’t be.